The Role of Human Papillomavirus in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Review)

Plast Aesthet Res 2016;3:132. ten.20517/2347-9264.2016.17 © 2016 Plastic and Artful Inquiry

Open Access Original Commodity

The role of human papillomavirus in oral squamous cell carcinoma

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial-Caput and Cervix Surgery, Academy Hospital Infanta Cristina, 06080 Badajoz, Spain.

Correspondence Address: Dr. Francisco A. Ramírez-Pérez, Section of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospital Infanta Cristina, Avenida de Elvas s/n, 06080 Badajoz, Spain. E-mail: francisco_alejandro_1987@hotmail.com

Views:17201 | Downloads:713 | Cited: 1 | Comments:0 | :0

1 | Comments:0 | :0

Received: 1 Apr 2016 | Accepted: 17 May 2016 | Published: 25 May 2016

Abstract

Aim: The causative role of human papillomavirus (HPV) has been established into the aetiology of oral squamous jail cell carcinoma (OSCC). Some authors believe that HPV can determinate the prognosis and module treatment response from this kind of malignancies.

Methods: Articles published in the concluding 10 years, focusing on the role of HPV in the evolution, molecular biology, prognosis and treatment of OSCC were reviewed.

Results: Thirty-nine articles from 252 were selected, highlighting 4 meta-assay, 3 prospective and two retrospective studies. According to its role in the development of cervical cancer, HPV is classified into a high risk for malignant lesions subtype and a low-grade malignant lesions subtype. Epidemiology and prevalence of HPV varies co-ordinate to the published data: big studies tend to take lower rates of HPV (< 50%) than smaller ones (0-100%). Interestingly, HPV+ patients are usually diagnosed at a younger age, mainly those with oropharyngeal tumours. There is a predilection for the oropharynx and Waldeyer band tumours. Regarding prognosis, OSCC HPV+ patients tend to have better consequence and handling response.

Conclusion: HPV divides OSCC in two types of tumours with different prognostic and therapeutic implications, with increased survival, better treatment response rates and lower gamble of decease and recurrences.

Keywords

Papillomavirus infections, carcinoma squamous cell, mouth

Introduction

Squamous jail cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common malignant lesion of the oral cavity and oropharynx. It is characterized past a multifactorial aetiology,[1-5] where the causative office of papillomavirus (HPV) has been established.[6] It is sexually acquired,[7] usually described in the tonsillar area,[8-10] affecting younger, non-drinkers and not-smokers patients.[11-13] DNA from virtually oncogenic chance HPV is detected in approximately 26% of all oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) throughout the world.[14]

The appearance of this kind of tumours has changed among the terminal decades. Some genotypes accept been suggested as the near probable causative agents of human papillomavirus, whose carcinogenic issue in oropharynx was first proposed by Syrjänen et al.[xv] in 1983 according to common morphological characteristics of HPV and immunohistochemistry. Later, this was confirmed by using new techniques such as "Southern Blot Hybridization".[sixteen,17] HPV has been proposed every bit a major risk cistron for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC),[vii,18] with a strong association in subjects with or without the established risks of smoking and alcohol.[vii]

The oncogenic potential of certain high-risk HPV genotypes is related to its ability of integrating DNA fragments (E5, E6 and E7) in the host prison cell, annulling the function of tumour suppressor factors such equally p21, p53 and pRb routes.[19] However, there are many ethno-geographical differences between the examined groups, with detection ranges from 0 to 100%.[18,20-24] Virus detection is also afflicted past the sensitivity of the diagnostic exam and the location of the lesion, which hard the clarification of the role of HPV and its carcinogenic potential.[vii,25]

Some authors non only involve the virus in the pathogenesis of OSCC, only likewise believe that it tin determine the prognosis and module treatment response.[26] The first type of HPV isolated in OSCC was HPV16 in the palatine tonsil, fabricated by Niedobitek et al.[27] in 1990. However, this is non the but subtype identified, varying co-ordinate to the analysed population sample.[28] Recently this type of HPV-positive tumours in the oral cavity was described as an entity with unlike molecular, clinical, etiological, pathological and prognostic characteristics.[vi,20-23,29-32]

Methods

A review of manufactures published in the last ten years (since February 29, 2016 until January 1, 2005) in the database of medical literature MEDLINE via PubMed search engine was performed. The following descriptors obtained from "DeCS" were used equally keywords: "Papillomavirus Infections", "Carcinoma, Squamous Cell" and "Mouth". All possible associations between them were used.

The main objective was to study the office of HPV in the evolution, molecular biology, prognosis and treatment of OSCC. We also provided special attending to detection and sampling techniques, risk factors, epidemiology, human relationship with other non-cancerous lesions and history of the virus.

Inclusion criteria were: (i) studies published betwixt the dates indicated; (ii) English language; (3) both observational and experimental studies; (4) reviews and meta-analyses; and (5) items that although published at an before date than the cut-off, are cited in the main revised. Exclusion criteria were: (1) publications that do not appear in the set date range and which are non mentioned in whatsoever of the included; (2) any type of non-English language; (iii) studies lacking internal or external validity; (four) editorials and case reports; (5) studies with a sample size lower than 30, or if information technology is non mentioned by any of the included; and (half dozen) articles that do non contain information on the main search object.

Results

We preliminarily establish 252 articles, of which only 39 were included and reviewed. Among these, 9 publications were highlighted: iv meta-analysis,[14,33-35] 3 prospective studies[32,36,37] and ii retrospective studies.[38,39] Chief results from these studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

Nine highlighted publications

| Author | Yr | Study | Objective | Number | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miller and Johnstone[33] | 2001 | Meta-analysis | To determine the significance of the relationship of HPV in the progressive development of oral cancer | four,680 | HPV is detected with increased frequency in oral dysplastic and carcinomatous epithelium in comparison with normal oral mucosa |

| Kreimer et al.[fourteen] | 2005 | Meta-analysis | To depict the prevalence and type distribution of HPV past anatomic cancer site | v,046 | Tumor site-specific HPV prevalence was higher among studies from North America compared with Europe and Asia |

| Ragin and Taioli[35] | 2007 | Meta-analysis | To study the overall human relationship between HPV infection and OS and DFS in HNSCC | 3,151 | The improved Os and DFS for HPV+ HNSCC patients is specific to the oropharynx; these tumours may have a distinct etiology from those tumours in not-oropharyngeal sites |

| Jayaprakash et al.[34] | 2011 | Meta-analysis | To provide a prevalence estimate for HPV-16/18 in OPD | 458 | HPV-sixteen/18 were 3 times more common in dysplastic lesions (OR, three.29; 95% CI, 1.95- five.53%) and invasive cancers (OR, iii.43; 95% CI, 2.07-5.69%), when compared to normal biopsie |

| Rosenquist et al.[32] | 2007 | Prospective | To evaluate the influence of unlike adventure factors for recurrence or the appearance of new second primary in the OSCC | 128 | High-risk HPV cases accept a higher gamble of recurrence/second primary tumours, but lower run a risk of death in intercurrent disease, compared with HPV- |

| Fakhry et al.[36] | 2008 | Prospective | To evaluate the association betwixt tumour HPV status with the therapeutic response and survival | 96 | HPV+ HNSCC respond better to QT and RT-QT, with ameliorate overall survival rate at two years and reduced risk of illness progression than HPV- |

| Rischin et al.[37] | 2011 | Prospective | To determine the prognostic significance of p16 and HPV in patients with OPC | 185 | HPV+ OPC is a distinct entity with a favorable prognosis (when compared with HPV-). When it is treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy |

| Ang et al.[38] | 2010 | Retrospective | To study the association between tumor HPV condition and survival in phase Three and 4 OPD | 743 | Among patients with OPC, tumor HPV status is a strong and independent prognostic factor for survival |

| Lassen et al.[39] | 2014 | Retrospective | To test the hypothesis that the bear on of HPV/p16 as well extends to non-OP tumours | ane,294 | The prognostic impact of HPV- associated p16-expression may be restricted to OPC merely |

Word

There is much written literature about the relationship of HPV virus and OSCC. Due to the great disparity of published data, it is very difficult to establish rightly the role HPV plays and its etiopathological, clinical and prognostic considerations. This tin be related to differences in written report populations (genetic, social and cultural factors) and the methodology of study and detection of virus.

There are many HPV genotypes identified, within which, over 130 are related to skin and mucosal lesions.[40] The first to propose the pathogenic human relationship of this type of virus with OSCC was Syrjänen et al.[15] in 1983. And the commencement type identified in head and neck was HPV16 in palatine tonsil carcinomas.[27] Since then, in that location accept been many published studies on detection and nigh its role in OSCC.

HPV molecular biology

HPV belongs to a heterogeneous group corresponding to the "Papillomaviridae" family unit.[41] It is characterized as a DNA-double stranded virus. It has a diameter of 50 μm and it is covered past an icosahedral capsid consisting of 72 capsomeres, without casing[42,43] and presents a particular tropism past keratinocytes, beingness the synthesis and expression of their genes linked to the level of their differentiation.[44]

At that place are different routes of infection, mainly sexual, vertical and cocky-inoculation; they all share the need for close contact to occur.[45,46] Manual from non-primates to humans is unknown to occur.[47,48]

To active the infection, the virus must reach the epithelial basal layer, where the specific integrin blastoff 6 receptor is present.[33] Once the infection becomes productive, cytopathic effects tin announced, first of all koilocytosis.[44] To make this happen, the patient's allowed response plays an of import role. During infection, viral antigen presentation is minimal and thus the infection tin can persist until years.[33] In immunocompetent patients lesions usually regress spontaneously, while in immunodeficient the incidence and persistence of them is commonly college.[49]

Regarding the oncological potential of the virus, there is much controversy about the true role played by the integration of viral Deoxyribonucleic acid into human epithelial cells. Several authors take investigated its pathogenesis in OSCC. According to its part in the development of cervical cancer, HPV is classified into a high run a risk for malignant lesions subtype (HPV sixteen, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73 and 82) and depression-grade malignant lesions subtype but related to benign lesions (HPV 6, 11, xiii, 32, 42, 43, 44).[33,50]

The HPV genome is divided into about eight open reading frames (ORFs) divided into three regions:[2,33] (1) early on region (E): it is required for replication, cell transformation and control of viral transcription; (2) belatedly region (Fifty): it encodes structural proteins; and (three) long control region (LCR): it is required for replication and transcription of viral Deoxyribonucleic acid.

In Due east, three proteins are encoded, which are frequently described as involved in the carcinogenesis related to the virus: pE7, pE6 and pE5.[ii,33,44] PE5 stimulates proliferation and inhibits apoptosis, while pE7 and pE6 deed as oncogenes.[2,33,47,48,51,52]

The terminal outcome is an induced and unregulated prison cell proliferation, with consequent immortality of the keratinocyte[nineteen] due to the integration and expression of the viral genome into the host jail cell. Chromosome aberrations and excessive production of viral Dna[53,54] all occur due to inhibition of tumor suppressor factors (p21, p53 and pRb roads).[19]

However, although the involvement of inhibition of tumor suppressor factor p53 in the carcinogenic effect of HPV seems to exist clear, there are some publications that question the relationship of p53 polymorphism with the adventure of oral cancer,[55] suggesting that HPV does non play an of import role oral lesions due to low detention in their analysed.[56-59] This could exist justified by population differences, sample size, detection techniques and tumor location. Some studies suggest that in HPV+ OSCC, p53 mutation is conditioned by tumor localization and expression of E6 and E7 viral genes, appearing a mutated p53 when the tumor is HPV+ but it does not express these genes (mainly oropharynx), or when the tumor is HPV-.[sixty,61]

Epidemiology and prevalence

Epidemiology and prevalence of HPV infection associated with OSCC varies according to the published data. Large studies tend to have lower rates of HPV (< 50%) than smaller studies (0-100%).[25,62] Miller and Johnstone[33] in a meta-analysis about 4,680 patients with OSCC from 94 reports reported that HPV was present in 46.v% of the cases (95% CI, 37.half-dozen-55.5%). Even so, the oral cavity was not the most often location, being surpassed by the oropharynx.[63,64]

Kreimer et al.[14] in a meta-analysis from 60 publications in 2005 (5,046 patients) reported that the overall prevalence of HPV in OSCC was 25.9% to 34.5%.[14,25] The prevalence of OSCC ranges from < 2% to 100%[10,25,57,65] and it may exist considering some studies practise not differentiate betwixt Parafine Embedded and Fresh Frozen biopsies or dissimilar classification criteria, including incorrectly OPSCC within the OSCC, making an overestimation.[25]

There is an association between the presence of HPV and historic period; patients older than 60 years take a lower HPV+ prevalence (29.four%) compared to patients under that age (77.eight%).[66] Within the OPSCC HPV+, HPV16 is higher in patients younger than fifty years.[67,68] In relationship to sexual behaviour, the risk of oral cancer increases in male patients with decreasing historic period of commencement intercourse, with increasing numbers of partners and history of genital warts.[69]

Regarding to etnogeographical differences, some authors suggest that Japanese studies tend to have the highest rate of HPV,[70,71] while Africans tend to take the lowest charge per unit.[59] Kreimer et al.[14] established that HPV+ prevalence was higher amongst studies from North America compared with those from Europe and Asia. In 2016, Mehanna et al.[72] conducted a prospective study of 801 patients with head and neck cancers. They established the geographic variability (differences betwixt continents) as an independent adventure factor for HPV+ prevalence of OPSCC. Information technology is most prevalent in Western Europe, when compared to Eastern Europe (37%, 155 of 422 vs. half-dozen%, 8 of 144; P < 0.0001) and Asia (37% vs. two%, iv of 217; P < 0.0001).

Regarding the genotype, the most prevalent is HPV16 (68.2-90%)[xiv,33,66] [Figures 1-iii] followed by HPV18 (34.1%).[14,73] But this varies depending on the series analysed and the techniques used, and that proportion may exist reversed, being higher HPV18.[28,59] Although the association between HPV and OSCC is described,[32,62,68,74-77] information technology is important to note that loftier-risk genotypes HPV16 accept been detected in normal oropharyngeal mucosa,[78,79,62] questioning this causal human relationship. In 2001, Mork et al.[80] defined HPV infection as a take a chance factor for OSCC, whose exposure may precede the occurrence of OPSCC in 10 years and older.

Figure one. The case of a lxx-year-old and ex-smoker female patient with a human papillomavirus+ head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nosotros can encounter an exophytic lesion three years of evolution on the left floor of the mouth, surpassing the midline, with a progressive growth. The patient has no dysphagia or dyspnea. We decide to take biopsies, obtaining the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma

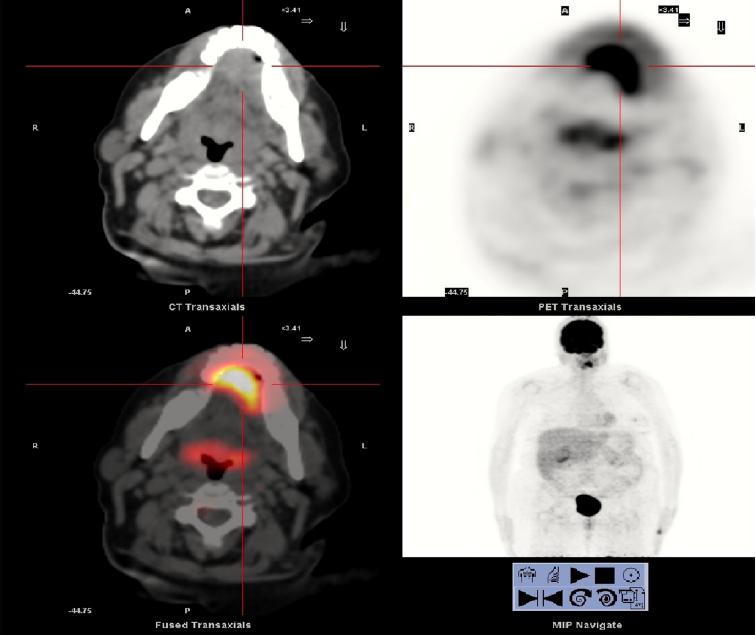

Figure 2. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography shows a mass in the left region of the anterior oral cavity floor, with marked increase glucose metabolism, most iii cm in diameter and high probability of malignancy. The other cervical structures have normal glucose metabolism, showing no other hypermetabolic neoplastic interest

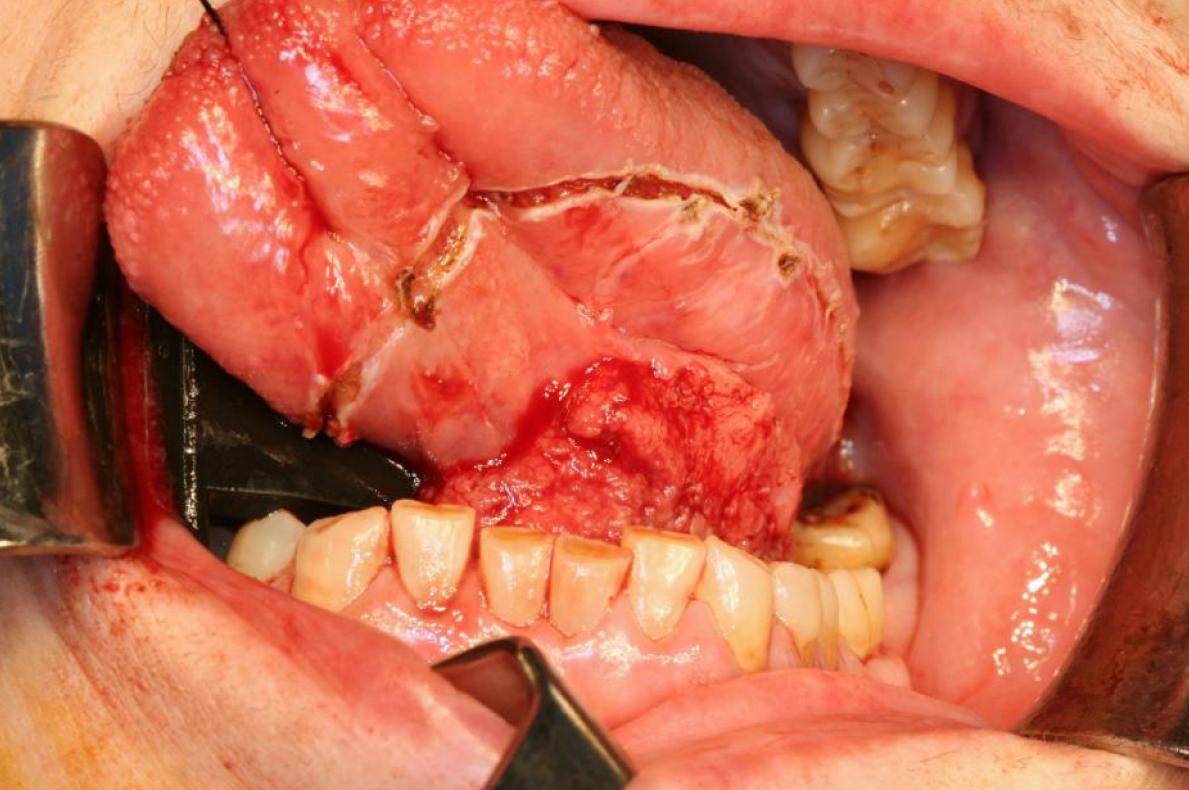

Figure 3. Intraoperative image. Subsequently performing tracheotomy, double functional bilateral cervix dissection, excision of the lesion with macroscopic margins higher up the centimeter and subsequent reconstruction with radial forearm flap was performed. Histological results reveals a pT3N0M0 human being papillomavirus 16+ squamous jail cell carcinoma, with shut resection margins, 6 mm thickness, with no vascular or perineural infiltration. After surgery, the patient received adjuvant radiotherapy. She is currently without signs of loco-regional recurrence

In the oropharynx in that location is no hard show linking HPV with alcohol or tobacco use, and the absence of synergism is the most accepted hypothesis,[81] suggesting ii means for the development of OPSCC, one derived from smoking with or without alcohol and another derived from the HPV inducted genomic instability.[31]

Most frequent location

HPV has a predilection for the oropharynx and the Waldeyer ring.[xiv,24,59] It is estimated that the almost frequent location for detecting papillomavirus Dna is the palatine tonsil and the base of the tongue, with a strong causal association,[14,82] independently of the influence of smoking or alcohol. Oropharyngeal HPV+ tumours appears in up to six times more often than in other tumours of the head and neck.[six] Snijders et al.[83] were the first to suggest the amygdala is linked with the HPV, in 1992.

Detection, diagnosis and typing techniques

Molecular assays are the gold standard for HPV identification,[84] mainly polymerase chain reaction (PCR),[85] specifically the reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) to measure viral mRNA E6 and E7 in fresh tissue.[86] It has a high sensitivity.[lxxx,85-88] It is fifty-fifty able to observe latent infections. Other tests that have been used for detection of HPV are "Southern Blot" (less sensitivity than PCR)[89] and in situ hybridization (ISH) (less sensitive and less expensive than PCR). Some authors accept proposed the combination of PCR with ISH, combining the advantages of the two tests: the high sensitivity of PCR and the ability of ISH to place and localize genomic sequences linked to HPV in this kind of tumours.[90,91]

P16 is a poly peptide used by some authors as a biomarker for HPV infection, which can exist expressed when viral Deoxyribonucleic acid is integrated into the host cell. Information technology reflects the functional effects derived from the inactivation of pRb, induced by E7. It is detected by immunohistochemistry staining and it tin be used as a predictor of HPV infection in OPSCC, even being proposed by some authors the detection of p16INK4A equally an initial test, followed past the detection of HPV in which are positive for this.[92-94]

Regarding to the sample being sent for testing, the most usually accustomed information technology is taking biopsies or tumour specimen analysis [Figure i]. This allows non only molecular analysis but as well morphological analysis of the piece, including all jail cell layers where the virus may be latently.[95] As a method of screening for epidemiological studies, Lawton et al.[96] reported that mouthwash is the technique of pick, although college performance past combining different sampling techniques is obtained.

Virus relationship with other oral lesions

Since the early 1980s some authors accept reported the presence of HPV not only in cancerous lesions of the oral cavity, but likewise in premalignant lesions.[15,97,98] Recently, the presence of HPV has been identified as an independent prognostic gene for survival in patients with OPSCC.[38] Miller and Johnstone[33] indicate that HPV (depression and high risk serotypes) are ii-3 times more detected in precancerous mucosa and almost 5 times more detected in carcinoma than in non-neoplastic mucosa: (i) 22.2% in benign leukoplakia; (2) 26.ii% in intraepithelial neoplasias; and (3) 46.5% in OSCC, with a detection probability of high-risk ones 2.8 times higher than depression gamble.

Jayaprakash et al.[34] published in 2011 a meta-assay about 458 oropharyngeal dysplasias, estimating that the prevalence of HPV16/18 is 24.5%. They reported that HPV16/18 were three times more common in dysplastic lesions (OR, 3.29; 95% CI, 1.95-5.53%) and invasive cancers (OR, 3.43; 95% CI, 2.07-5.69%), when compared to normal biopsies. In addition, they found these two genotypes are at least two.5 times more common in men than in women. Within oral leukoplakia, proliferative verrucous leukoplakia is believed to accept a stronger relationship with HPV[44] mainly 16, with a range of onset between 10% and 85%,[99,100] and higher rate of cancerous transformation.[101] Some authors have likewise reported a human relationship between lichen planus and HPV, ranging from 0 to 100%,[102] which indicates the existing controversy well-nigh this association.

Many publications are studying virus connection with benign lesions or even in normal mucosa, varying its prevalence depending on the technique used, many times no PCR techniques are used, which may underestimate measurements. As a summary:

Advent in normal mucosa: varies between 0 and 81%.[78,103] It may appear subclinical or latent,[104] being detected past the extreme sensitivity of the PCR and may be or non related to the emergence of a future lesion.

Squamous papilloma: clinically ofttimes duplicate from common warts. HPV genotypes half-dozen and xi are most ofttimes associated, detected past ISH.[105]

Condyloma accuminatum: it is a sexually transmitted infection and it is usually related to HPV half dozen and 11 infection, varying its positivity between 75% and 85% in oral lesions.[106,107] Furthermore information technology is too related to the HPV 16.[108,109] Information technology is usually present in HIV+ patients.[110]

Common wart (verruca vulgaris): oral lesions commonly upshot from autoinoculation from the fingers. It usually occurs in children. The HPV two is described equally the most frequently related, followed by HPV 57,[106,111] detected most of the time with no PCR techniques betwixt 80% and xc%. Other authors with more recent publications detected more than frequently HPV2 and 4.[109]

Focal epithelial hyperplasia (Heck's disease): they usually occur in children and young adults. There is usually genetic predisposition.[112] HPV13 (20%) and HPV32 (60%) are related to those lesions.[113-115]

Prognosis and treatment

There is much controversy almost the office that infection past the HPV plays in the prognosis and treatment of patients with OSCC. Most of the published studies are retrospective. But they do more often than not conclude that the presence of HPV divides these tumours in two different entities with dissimilar prognostic and therapeutic implications. The most normally accepted is that patients with OPSCC HPV+ have a better prognosis due to increased survival, showing better treatment response rates.[36,38,63,116-118]

The most cited paper in the literature is the one published past Fakhry et al.[36] in 2008. They conducted a prospective phase 2 study of 96 patients with oral, oropharyngeal and laryngeal SCC. All patients received 2 cycles of induction chemotherapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by concurrent weekly paclitaxel and radiotherapy. They detected HPV (types 16, 33 and 35) with PCR and ISH in forty% of all patients. They compared their response to treatment with HPV-: OSCC HPV+ have amend respond to chemotherapy (82% vs. 55%, difference = 27%, 95% CI, ix.iii-44.7%; P = 0.01) and chemo-radiotherapy (84% vs. 57%, difference = 27%, 95% CI, ix.7- 44.iii%; P = 0.007).

Patients with OSCC HPV + have a better overall survival charge per unit at two years [95% (95% CI, 87-100%) vs. 62% (95% CI, 49-74%), (difference = 33%, 95% CI, 18.6- 47.four%; P = 0.005, log-rank test)] and a lower risk of disease progression than HPV- [Hazard Ratio (HR), 0.27; 95% CI, 0.x-0.75%].

In 2007, Ragin and Taioli[35] performed a meta-analysis of 37 studies, which conclude that patients with OSCC HPV+ had a lower take a chance of death (HR = 0.85 target; 95% CI, 0.7-one.0) and lower risk of recurrence (Hr = 0.62% target; 95% CI, 0.5-0.viii) than in HPV-. Regarding OPSCC they conclude that HPV+ had a reduced adventure of death of 28% (Target HR 0.72; 95% CI, 0.5-1.0) compared with HPV- with a similar effect for affliction-free survival (Meta Hour, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.4-0.7).

In the same year, Rosenquist et al.[32] conducted a prospective report of cases and controls over 128 Swedish patients with OPSCC to evaluate the influence of unlike risk factors for recurrence or appearance of new second primaries in the first 3 years later the diagnosis. They establish, dissimilar other published studies that high-gamble HPV+ cases had a college risk of recurrence/second master neoplasm, but lower risk of death in intercurrent disease, compared with HPV- ones.

In 2008, Worden et al.[119] conducted a study about the response to treatment of 66 patients with OPSCC. They plant that the presence of HPV was significantly associated with response to chemotherapy (P = 0.001), chemo-radiotherapy (P = 0.005), with better overall survival (P = 0.007) and disease-gratuitous survival (P = 0.008). They conclude that chemotherapy followed by chemo-radiations therapy is an effective handling especially in patients with HPV + OPSCC.

In 2010, Ang et al.[38] conducted a retrospective study of the association betwixt tumor HPV status and survival amidst 743 patients with phase III or 4 OPSCC who were enrolled in a randomized trial comparing treatment with accelerated-fractionation RT+ cisplatin vs. standard-fractionation RT+ cisplatin. Amongst 323 OPSCC, 63.8% were HPV+, which presented better three-year rates of overall survival (82.iv% vs. 57.1% amid patients with HPV- negative tumours; P < 0.001 by the log-rank test) and they also had a 58% reduction in the risk of death (60 minutes, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.27 to 0.66). They concluded that among patients with OPSCC, tumor HPV status is a stiff and independent prognostic factor for survival.

Some authors accept studied the prognostic influence of some biomarkers related to HPV infection in OSCC. I of the most studied biomarkers is p16, being observed that p16+ and HPV+ patients have a better overall survival compared with HPV- or HPV+ simply p16-.[93] This was corroborated in the prospective stage Three study of concomitant chemotherapy published in 2011 by Rischin et al.[37] In a sample of 465 patients with OPSCC stage 3 or 4, 172 were analysed with evaluable HPV and p16INK4A condition, and 185 with eligible p16 status. They randomized RT+ cisplatin with or without tirapazamine, concomitantly. They establish that p16+ tumours compared to p16- presented: (1) higher rates of overall survival at 2 years (91% vs. 74%; HR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.17-0.74; P = 0.004); (2) higher rates of relapse-free survival (87% vs. 72%; HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.xx-0.74; P = 0.003); and (three) lower loco-regional recurrence and death rates from other causes. They besides observed a tendency in favour of tirapazamine grouping in terms of improved loco-regional control affliction in p16- patients (Hour, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.09-1.24; P = 0.13). They concluded that OPSCC HPV+ take a favourable prognosis when treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy, compared to HPV-.

In 2014, Lassen et al.[39] published a retrospective report among 1,294 Danish patients with advanced stage OPSCC. They observed that p16 positivity was significantly higher in oropharyngeal than not-oropharyngeal SCC (P < 0.0001). OPSCC p16+ presented a statistically pregnant improvement in loco-regional affliction control with chief RT [HR (95% CI), 0.38 (0.29-0.49)], complimentary survival events [60 minutes (95% CI), 0.44 (0.35-0.56)] and overall survival [60 minutes (95% CI), 0.38 (0.29-0.49)], unlike in non-OP.

Future therapeutic lines

HPV+ OSCC response to RT, chemotherapy and the combination of both are topics widely approached in the literature and specialized forums. However, little or zero is known about immunotherapy techniques and their effectiveness. In 2015, Rosenthal et al.[120] published a retrospective assessment of the IMCL-9815 study, trying to find if there were whatever differences in treatment patients with RT alone vs. RT+ cetuximab, in a serial of 182 OSCC patients, in relation to the presence or absence of HPV and p16. They concluded that the improver of cetuximab to RT improved clinical outcomes regardless of p16 or HPV positivity. They also indicated that p16 does not predicted response to cetuximab.

Dissimilar cervical cancer, regarding OSCC at that place is not much literature on the use of HPV vaccines to treat these tumours. The effectiveness of the HPV vaccine against OSCC is not yet proven.

In determination, there is much controversy nigh the carcinogenic potential of HPV. Its mechanism usually involves the pE7 and pE6 proteins, which tin can delete p53, p21 and pRb routes.

HPV+ patients are ordinarily diagnosed at a younger age, mainly those with oropharyngeal tumours, presenting positivity starting time of all for HPV16 > HPV18, although information technology varies depending on the population and the exam used to notice the infection.

For more diagnostic performance, the most advisable is to use the combination of several techniques. P16 positivity needs to be mentioned in special attending as a predictor of HPV infection in the OPSCC for their prognostic and therapeutic considerations.

HPV tin announced in normal mucosa, benign and precancerous lesions.

The most commonly accustomed is that the presence of HPV divides OSCC, mainly oropharyngeal, in ii types of tumours with different prognostic and therapeutic implications.

Despite the slap-up controversy in prognosis, near studies tend to indicate that HPV+ OSCC have an increased survival, ameliorate treatment response rates, lower chance of death and lower chance of recurrence [Effigy 3].

The oropharyngeal region should exist analysed separately. OPSCC HPV+ tend to answer better to radio-chemotherapy treatments, considering the HPV positivity as a strong and independent survival prognostic cistron. In addition, if p16+, these tumours tend to have better survival and loco-regional illness-control.

Future enquiry should evaluate the possibility of new treatments.

Financial back up and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

In that location are no conflicts of interest.

References

-

i. Scully C, Field JK, Tanzawa H. Genetic aberrations in oral or head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (SCCHN): 1. Carcinogen metabolism, DNA repair and cell cycle control. Oral Oncol 2000;36:256-63.

DOI -

two. Syrjänen S, Lodi 1000, von Bültzingslöwen I, Aliko A, Arduino P, Campisi G, Challacombe S, Ficarra G, Flaitz C, Zhou HM, Maeda H, Miller C, Jontell M. Homo papillomavirus in oral carcinoma and oral potentially malignant disorders: a systematic review. Oral Dis 2011;17 Suppl 1:58-72.

DOIPubMed -

iii. Pande P, Soni South, Kaur J, Agarwal S, Mathur M, Shukla NK, Ralhan R. Prognostic factors in betel and tobacco related oral cancer. Oral Oncol 2002;38:491-9.

DOI -

4. Frances chi Southward, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Conti E, Dal Maso L, Barzan L, Talamini R. Comparison of the effect of smoking and alcohol drinking betwixt oral and pharyngeal cancer. Int J Cancer 1999;83:1-4.

DOI -

5. La Vecchia C, Tavani A, Franceschi S, Levi F, Corrao G, Negri E. Epidemiology and prevention of oral cancer. Oral Oncol 1997;33:302-12.

DOI -

half dozen. Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, Zahurak ML, Daniel RW, Viglione K, Symer DE, Shah KV, Sidransky D. Evidence for causal clan between human being papillomavirus and a subset of caput and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:709-20.

DOIPubMed -

7. D'Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, Koch WM, Westra WH, Gillison ML. Case-control report of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1944-56.

DOIPubMed -

8. Hammarstedt L, Lindquist D, Dahlstrand H, Romanitan M, Dahlgren LO, Joneberg J, Creson N, Lindholm J, Ye W, Dalianis T, Munck-Wikland Due east. Human papillomavirus as a adventure gene for the increase in incidence of tonsillar cancer. Int J Cancer 2006;110:2620-iii.

DOIPubMed -

9. Mellin H, Friesland Due south, Lewensohn R, Dalianis T, Munck-Wikland E. Human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA in tonsillar cancer: clinical correlates, take chances of relapse, and survival. Int J Cancer 2000;89:300-four.

DOI -

10. Paz IB, Cook N, Odom-Maryon T, Xie Y, Wilczynski SP. Human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer: an association of HPV 16 with squamous cell carcinoma of Waldeyer'due south tonsillar ring. Cancer 1997;79:595-604.

DOI -

11. Shiboski CH, Schmidt BL, Hashemite kingdom of jordan RC. Tongue and tonsil carcinoma: increasing trends in the U.s. population ages twenty-44 years. Cancer 2005;103:1843-9.

DOIPubMed -

12. Canto MT, Devesa SS. Oral crenel and pharynx cancer incidences rates in the United Sates, 1975-1998. Oral Oncol 2002;38:610-7.

DOI -

thirteen. Frisch 1000, Hjalgrim H, Jaeger AB, Biggar RJ. Irresolute patterns of tonsillar squamous jail cell carcinoma in the United States. Cancer Causes Command 2000;eleven:489-95.

DOIPubMed -

fourteen. Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi Due south. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous jail cell carcinoma worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;fourteen:467-75.

DOIPubMed -

15. Syrjänen K, Syrjänen South, Lamberg M, Pyrhönen S, Nuutinen J. Morphological and inmunohistochemical testify suggesting human papillomavirus (HPV) interest in oral squamous cell carcinogenesis. Int J Oral Surg 1983;12:418-24.

DOI -

16. Franceschi S, Mu-oz N, Bosch XF, Snijders PJ, Walboomers JM. Human papillomavirus and cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract: a review of epidemiological and experimental evidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1996;five:567-75.

PubMed -

17. Lönging T, Ikenberg H, Becker J, Gissmann L, Hoepfer I, zur Hausen H. Assay of oral papillomas, leukoplakias, and invasive carcinomas for human papillomavirus blazon related Dna. J Invest Dermatol 1985;84:417-20.

DOI -

eighteen. Tran Due north, Rose BR, O'Brien CJ. Role of homo papillomavirus in the etiology of head and neck cancer. Caput Neck 2007;29:64-70.

DOIPubMed -

19. Ragin CC, Modugno F, Gollin SM. The epidemiology and adventure factors of head and neck cancer: a focus on human papillomavirus. J Dent Res 2007;86:104-fourteen.

DOIPubMed -

20. Gillson ML. Homo papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer is a distinct epidemiologic, clinical and molecular entity. Semin Oncol 2004;31:744-54.

DOI -

21. Dahstrand H, Dahlgren L, Lindquist D, MunckWikland E, Dalianis T. Presence of human papillomavirus in tonsillar cancer is a favourable prognostic factor for clinical upshot. Anticancer Res 2004;24:1829-35.

-

22. Sanderson RJ, Ironside JA. Squamous prison cell carcinomas of the head and neck. BMJ 2002;325:822-seven.

DOI -

23. Gillison ML, Lowy DR. A causal office for homo papillomavirus in head and neck cancer. Lancet 2004;365:1488-nine.

DOI -

24. Miller CS, White DK. Human Papillomavirus expression in oral mucosa, premalignant conditions, and squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1996;82:57-68.

DOI -

25. Termine Northward, Panzarella V, Falaschini S, Russo A, Matranga D, Lo Muzio Fifty, Campisi 1000. HPV in oral squamous cell carcinoma vs. head and neck squamous prison cell carcinoma biopsies: a meta-analysis (1988-2007). Ann Oncol 2008;xix:1681-ninety.

DOIPubMed -

26. Charfi Fifty, Jouffroy T, de Cremoux P, Le Peltier N, Thioux M, Fréneaux P, Point D, Girod A, Rodriguez J, Sastre-Garau X. Two types of squamous cell carcinoma of the palatine tonsil characterized by distinct etiology, molecular features and outcome. Cancer Lett 2008;260:72-8.

DOIPubMed -

27. Niedobitek Thousand, Pitteroff Southward, Herbst H, Shepherd P, Finn T, Anagnostopoulos I, Stein H. Detection of human papillomavirus type 16 Dna in carcinomas of the palatine tonsil. J Clin Pathol 1990;43:918-21.

DOIPubMed PMC -

28. Soares RC, Oliveira MC, de Souza LB, Costa Ade L, Pinto LP. Detection of HPV DNA and inmunohistochemical expression of jail cell cycle proteins in oral carcinoma in a population of Brazilian patients. J Appl Oral Sci 2008;sixteen:340-4.

DOIPubMed PMC -

29. El-Mofty SK, Lu DW. Prevalence of human papillomavirus type xvi DNA in squamous prison cell carcinoma of the palatine tonsil, and not the oral cavity, in young patients: a distinct clinicopathologic and molecular disease entity. AM J Surg Pathol 2003;27:1463-70.

DOIPubMed -

xxx. El-Mofty SK, Patil S. Man papillomavirus (HPV)-related oropharyngeal nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma: characterization of a distint phenotype. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pahol Oral Radiol Endod 2006;101:339-45.

DOIPubMed -

31. Chen SF, Yu FS, Chang YC, Fu E, Nieh Due south, Lin YS. Part of human papillomavirus infection in carcinogenesis of oral squamous cell carcinoma with evidences of prognostic clan. J Oral Pathol Med 2012;41:9-15.

DOIPubMed -

32. Rosenquist K, Wennerberg J, Annertz Yard, Schildt EB, Hansson BG, Bladström A, Andersson G. Recurrence in patients with oral and oropharyngeal squamous prison cell carcinoma: human papillomavirus and other risk factors. Acta Otolaryngol 2007;127:980-7.

DOIPubMed -

33. Miller CS, Johnstone BM. Human being papillomavirus as a risk factor for oral squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001;91:622-35.

DOIPubMed -

34. Jayaprakash V, Reid Chiliad, Hatton Due east, Merzianu Grand, Rigual Due north, Marshall J, Gill S, Frustino J, Wilding M, Loree T, Popat Southward, Sullivan One thousand. Human papillomavirus types 16 and eighteen in epithelial dysplasia of oral cavity and oropharynx: a meta-analysis, 1985-2010. Oral Oncol 2011;47:1048-54.

DOIPubMed PMC -

35. Ragin CC, Taioli E. Survival of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in relation to human papillomavirus infection: review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2007;121:1813-20.

DOIPubMed -

36. Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, Cmelak A, Ridge JA, Pinto H, Forastiere A, Gillison ML. Improved survival of patients with homo papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:261-9.

DOIPubMed -

37. Rischin D, Young RJ, Fisher R, Play a joke on SB, Le QT, Peters LJ, Solomon B, Choi J, O'Sullivan B, Kenny LM, McArthur GA. Prognostic significance of p16INK4A and human papillomavirus in patients with oropharyngeal cancer treated on TROG 02.02 phase Iii trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4142-8.

DOIPubMed PMC -

38. Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, Westra WH, Chung CH, Hashemite kingdom of jordan RC, Lu C, Kim H, Axelrod R, Silverman CC, Redmond KP, Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:24-35.

DOIPubMed PMC -

39. Lassen P, Primdahl H, Johansen J, Kristensen CA, Andersen E, Andersen LJ, Evensen JF, Eriksen JG, Overgaard J; Danish Head and Cervix Cancer Group (DAHANCA). Impact of HPV-associated p16-expression on radiotherapy event in avant-garde oropharynx and non-oropharynx cancer. Radiother Oncol 2014;113:310-six.

DOIPubMed -

40. De Villiers EM. Papillomavirus and HPV typing. Clin Dermatol 1997;15:199-206.

DOI -

41. Van Regenmortel MHV FC, Fauquet CM, Bishop DHL, Carsten EB, Estes MK, Lemon SM, Maniloff J, Mayo MA, McGeoch DJ, Pringle CR, Wickner RB. Virus taxonomy: nomenclature and nomenclature of viruses. 7th report of the International Commission on Taxonomy of Viruses New York, San Diego: Academic Press; 2000.

-

42. Howley PM. Role of the human papillomaviruses in human cancer. Cancer Res 1991;51:S5019-22.

-

43. Cobb MW. Homo papillomavirus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:547-66.

DOI -

44. Campsini G, Panzarella V, Giuliani M, Lajolo C, Di Fede O, Falaschini Due south, Di Liberto C, Scully C, Lo Muzio L. Human being papillomavirus: its identikit and controversial role in oral oncogenesis, premalignant and malignant lesions (Review). Int J Oncol 2007;30:813-23.

-

45. Cason J, Kaye J, Pakarian F, Raju KS, Best JM. HPV-16 manual. Lancet 1995;345:197-8.

DOI -

46. Mindel A, Tideman R. HPV transmission - still feeling the fashion. Lancet 1999;354:2097-8.

DOI -

47. Hiller T, Iftner T. The human papillomavirus. In: Prendiville W, Davies P, editors. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. The Health Professional person'southward HPV Handbook. London and New York: Taylor & Francis; 2004. pp. 11-26.

-

48. Antonsson A, Forslund O, Ekburg H, Sterner G, Hanson BG. The ubiquity and impressive genomic diversity of human being skin papillomavirus suggest a commensalic nature of these viruses. J Virol 2000;74:11636-41.

DOIPubMed PMC -

49. Chang F. Function of papillomaviruses. J Clin Pathol 1990;43:269-76.

DOIPubMed PMC -

fifty. World Health Organization, International Bureau for Research on Cancer (IARC). Human papillomavirus. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Rsk Hum 2007;90:47–79,113–7.

-

51. De Villiers EM, Gunst K. Characterization of seven novel man papillomavirus types isolated from cutaneous tissue, only also present in mucosal lesions. J Gen Virol 2009;90:1994-2004.

DOIPubMed -

52. De Villiers EM, Faquet C, Banker TR, Bernard HU, Zur Hausen H. Nomenclature of papillomaviruses. Virology 2004;324:17-27.

DOIPubMed -

53. Munger K, Werness BA, Dyson N, Phelps WC, Harlow Eastward, Howley PM. Circuitous germination of human papillomavirus E7 proteins with the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor factor product. EMBO J 1989;8:4099-105.

PubMed PMC -

54. Werness BA, Levine AJ, Howley PM. Association of human being papillomavirus types sixteen and 18 E6 proteins with p53. Science 1990;248:76-9.

DOIPubMed -

55. Saini R, Tang Th, Zain RB, Cheong SC, Musa KI, Saini D, Ismail AR, Abraham MT, Mustafa WM, Santhanam J. Meaning association of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) but not of p53 polymorphisms with oral squamous jail cell carcinomas in Malaysia. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2011;137:311-xx.

DOIPubMed -

56. Ishibashi M, Kishino Thousand, Sato South, Morii E, Ogawa Y, Aozasa K, Kogo K, Toyosawa South. The prevalence of human being papillomavirus in oral premalignant lesions and squamous prison cell carcinoma in comparing to cervical lesions used as a positive control. Int J Clin Oncol 2011;sixteen:646-53.

DOIPubMed -

57. Khvidhunkit SP, Buajeeb W, Sanguasnion S, Poomsawat South, Weerapradist W. Detection of homo papillomavirus in oral squamous cell carcinoma, leukoplakia and lichen planus in thai patients. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev 2008;9:771-5.

-

58. Rivero ER, Nunes FD. HPV in oral squamous prison cell carcinomas of Brazilian population: amplification by PCR. Braz Oral Res 2006;twenty:21-4.

DOI -

59. Male child S, Van Rensburg EJ, Engelbrecht Southward, Dreyer L, van Heerden M, van Heerden W. HPV detection in master intra-oral squamous cell carcinomas-commensal, aetiological agent or contamination? J Oral Pathol Med 2008;35:86-90.

DOIPubMed -

sixty. Wiest T, Schwartz E, Enders C, Flechtenmacher C, Bosch FX. Involvement of intact HPV16 E6/E7 gene expression in head and neck cancers with unaltered p53 condition and perturbed pRb jail cell cycle control. Oncogene 2002;21:1510-7.

DOIPubMed -

61. van Houten VM, Snijders PJ, van den Brekel MW, Kummer JA, Meijer CJ, van Leeuwen B, Denkers F, Smeele LE, Snow GB, Brakenhoff RH. Biological evidence that human papillomaviruses are etiologically involved in a subgroup of head and cervix squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer 2001;93:232-5.

DOIPubMed -

62. Cox One thousand, Maitland N, Scully C. Human being Herpes simplex-1 and papillomavirus type xvi homologous DNA sequences in normal, potentially malignant and malignant oral mucosa. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1993;29B:215-ix.

DOI -

63. Gillson ML, D'Souza Grand, Westra W, Sugar E, Xiao Westward, Begum S, Viscidi R. Distinct risk cistron profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus blazon 16-negative head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:407-20.

DOIPubMed -

64. Pannone G, Santoro A, Papagerakis S, Lo Muzio L, De Rosa M, Bufo P. The role of man papillomavirus in the pathogenesis of head and neck squamous jail cell carcinoma: an overview. Infect Agents Cancer 2011;6:4.

DOIPubMed PMC -

65. Van Rensburg EJ, Engelbrecht S, Van Heerden WT, Raubennheimer EJ, Schoub BD. Homo papillomavirus DNA in oral squamous jail cell carcinomas from African population sample. Anticancer Res 1996;16:969-73.

PubMed -

66. Cruz IB, Snijders PJ, Steenbergen RD, Meijer CJ, Snow GB, Walboomers JM, van der Waal I. Historic period-dependence of human papillomavirus DNA presence in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1996;32B:55-62.

DOI -

67. Smith EM, Ritchie JM, Pawlita M, Rubenstein LM, Haugen TH, Turek LP, Hamsikova E. Human papillomavirus seropositivity and risks of head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer 2007;120:825-32.

DOIPubMed -

68. Smith EM, Ritchie JM, Summersgill KF, Klussmann JP, Lee JH, Wang D, Haugen Th, Turek LP. Historic period, sexual behaviour and human papillomavirus infection in oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. Int J Cancer 2004;108:766-72.

DOIPubMed -

69. Schwartz SM, Daling JR, Doody DR, Wipf GC, Carter JJ, Madeleine MM, Mao EJ, Fitzgibbons ED, Huang S, Beckmann AM, McDougall JK, Galloway DA. Oral cancer risk in relation to sexual history and evidence of human papillomavirus infection. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998;ninety:1626-36.

DOIPubMed -

70. Zhang ZY, Sdek P, Cao J, Chen WT. Homo papillomavirus type 16 and xviii Deoxyribonucleic acid in oral squamous cell carcinoma and normal mucosa. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;33:71-4.

DOIPubMed -

71. Sugiyama M, Bhawal UK, Kawamura One thousand, Ishioka Y, Shigeishi H, Higashikawa K, Kamata N. Homo papillomavirus-16 in oral squamous cell carcinoma: clinical correlates and five-twelvemonth survival. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;45:116-22.

DOIPubMed -

72. Mehanna H, Franklin N, Compton N, Robinson Thousand, Powell Northward, Biswas-Baldwin Northward, Paleri V, Hartley A, Fresco L, Al-Booz H, Junor Due east, El-Hariry I, Roberts S, Harrington Yard, Ang KK, Dunn J, Woodman C. Geographic variation in human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer: data from 4 multinational randomized trials. Head Neck 2016;38 Suppl ane:E1863-9.

DOIPubMed PMC -

73. Mathew A, Mody RN, Patait MR, Razooki AA, Varghese NT, Saraf K. Prevalence and relationship of human papilloma virus blazon s16 and type 18 with oral squamous cell carcinoma and oral leukoplakia in fresh scrapings: a PCR written report. Indian J Med Sci 2011;65:212-21.

DOIPubMed -

74. Hansson BG, Rosenquist K, Antonsson A, Wennerberg J, Schildt EB, Bladström A, Andersson G. Strong clan between infection with human being papillomavirus and oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a population-based case-control report in southern Sweden. Acta Otolaringol 2005;125:1337-44.

DOIPubMed -

75. Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Pawlita One thousand, Lissowska J, Kee F, Balaram P, Rajkumar T, Sridhar H, Rose B, Pintos J, Fernández Fifty, Idris A, Sánchez MJ, Nieto A, Talamini R, Tavani A, Bosch FX, Reidel U, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ, Viscidi R, Mu-oz N, Franceschi S; IARC Multicenter Oral Cancer Study Group. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: the International Bureau for Inquiry on Cancer multicenter written report. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:1772-83.

DOIPubMed -

76. Smith EM, Ritchie JM, Summersgill KF, Hoffman HT, Wang DH, Haugen TH, Turek LP. Human papillomavirus in oral exfoliated cells and chance of head and cervix cancer. J Nath Cancer Inst 2004;96:449-55.

DOI -

77. Dahlstrom KR, Adler-Storthz K, Etzel CJ, Liu Z, Dillon L, El-Naggar AK, Spitz MR, Schiller JT, Wei Q, Sturgis EM. Homo papillomavirus blazon xvi infection and squamous prison cell carcinoma of the head and cervix in never-smokers: a matched pair analysis. Clin Cancer Res 2003;nine:2620-6.

PubMed -

78. Terai 1000, Hashimoto K, Yoda K, Sata T. High prevalence of human being papillomaviruses in the normal oral cavity of adults. Oral Microbiol Immunol 1999;xiv:201-5.

DOIPubMed -

79. Kurose K, Terai One thousand, Soedarsono Northward, Rabello D, Nakajima Y, Burk RD, Takagi Yard. Low prevalence of HPV infection and its natural history in normal oral mucosa among volunteers on Miyako Island, Nihon. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004;98:91-6.

DOIPubMed -

80. Mork L, Prevarication AK, Glattre E, Hallmans G, Jellum E, Koskela P, Møller B, Pukkala E, Schiller JT, Youngman L, Lehtinen M, Dillner J. Homo papillomavirus infection every bit a risk factor for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and cervix. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1125-31.

DOIPubMed -

81. Shanesmith R, llen RA, Moore WE, Kingma DW, Caughron SK, Gillies EM, Dunn ST. Comparisson of 2 line blot assays for defining HPV genotypes in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2011;70:240-5.

DOIPubMed -

82. Pintos J, Blackness MJ, Sadeghi N, Ghadirian P, Zeitouni AG, Viscidi RP, Herrero R, Coutle′e F, Franco EL. Human papillomavirus infection and oral cancer: a case-control study in Montreal, Canada. Oral Oncol 2008;44:242-50.

DOIPubMed -

83. Snijders PJ, Cromme FV, van den Brule AJ, Schrijnemakers HF, Snow GB, Meijer CJ, Walboomers JM. Prevalence and expression of human papillomavirus in tonsillar carcinomas, indicating a possible viral etiology. Int J Cancer 1992;51:845-50.

DOIPubMed -

84. Zaravinos A, Mammas IN, Sourvinos One thousand, Spandidos DA. Molecular detection methods of human papillomavirus (HPV). Int J Biol Markers 2009;24:215-22.

DOIPubMed -

85. Giovannelli Fifty, Lama A, Capra G, Giordano V, Aricò P, Ammatuna P. Detection of homo papillomavirus Deoxyribonucleic acid in cervical samples: analyses of the new PGMY-PCR compared to the hybrid capture Two and MY-PCR assays and a two-step nested PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 2004;42:3861-4.

DOIPubMed PMC -

86. Chernock RD, El-Mofty SK, Thorstad WL, Parvin CA, Lewis JS Jr. HPV-related nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: utility of microscopic features in predicting patient outcome. Head Neck Pathol 2009;3:186-94.

DOIPubMed PMC -

87. Venuti A, Badaracco G, Rizzo C, Mafera B, Rahimi Southward, Vigili M. Presence of HPV in head and neck tumours: high prevalence in tonsillar localization. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2004;23:561-6.

PubMed -

88. Remmerbach TW, Brinckmann UG, Hemprich A, Chekol M, Kühndel K, Liebert UG. PCR detection of human papillomavirus of the mucosa: comparisation between MY09/11 and GP5+/6+ primer sets. J Clin Virol 2004;30:302-8.

DOIPubMed -

89. Mckaig RG, Baric RS, Olshan AF. Human papillomavirus and head and neck cancer: epidemiology. Caput Neck 1998;xx:250-65.

DOI -

90. Koyama M, Uobe K, Tanaka A. Highly sensitive detection of HPV-DNA in alkane sections of homo oral carcinomas. J Oral Pathol Med 2007;36:eighteen-24.

DOIPubMed -

91. Uobe K, Masuno K, Fang Twelvemonth, Li LJ, Wen YM, Ueda Y, Tanaka A. Detection of HPV in Japanese and Chinese oral carcinomas by in situ PCR. Oral Oncol 2001;37:146-52.

DOI -

92. Pannone G, Rodolico Five, Santoro A, Lo Muzio L, Franco R, Botti G, Aquino G, Pedicillo MC, Cagiano S, Campisi G, Rubini C, Papagerakis S, De Rosa 1000, Tornesello ML, Buonaguro FM, Staibano S, Bufo P. Evaluation of a combined triple method to observe causative HPV in oral and oropharyngeal squamous prison cell carcinomas: p16 Immunohistochemistry, Consensus PCR HPV-Deoxyribonucleic acid, and In Situ Hybridization. Infect Agent Cancer 2012;vii:4.

DOIPubMed PMC -

93. Schache AG, Liloglou T, Take a chance JM, Filia A, Jones TM, Sheard J, Woolgar JA, Helliwell TR, Triantafyllou A, Robinson Chiliad, Sloan P, Harvey-Woodworth C, Sisson D, Shaw RJ. Evaluation of human papilloma virus diagnostic testing in oropharyngeal squamous jail cell carcinoma: sensitivity, specificity, and prognostic discrimination. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:6262-71.

DOIPubMed PMC -

94. Husnjak K, Grce M, Magdic L, Pavelic Thousand. Comparaison of 5 dissimilar polymerase chain reaction methods for detection of human papillomavirus in cervical cell specimens. J Virol Methods 2000;88:125-34.

DOI -

95. Longworth MS, Laimins LA. Pathogenesis of human being papillomavirus in differentiating epithelia. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2004;68:362-72.

DOIPubMed PMC -

96. Lawton Thousand, Thomas Due south, Schonrock J, Monsour F, Frazer I. Man papillomaviruses in normal mucosa: a comparison of methods for simple collection. J Oral Pathol Med 1992;21:265-nine.

DOIPubMed -

97. Loning T, Ikenberg H, Becker J, Gissmann 50, Hoepfer I, zur Hausen H. Analysis of oral papillomas, leukoplakias, and invasive carcinomas for human papillomavirus blazon related Dna. J Invest Dermatol 1985;84:417-xx.

DOIPubMed -

98. de Villiers Em, Weidauer H, Otto H, zur Hausen H. Papillomavirus Dna in human tongue carcinomas. Int J Cancer 1985;36:575-eight.

DOIPubMed -

99. Palefsky JM, Silverman S Jr, Abdel-Salaam M, Daniels TE, Greenspan JS. Association between proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and infection with human papillomavirus blazon xvi. J Oral Pathol Med 1995;24:193-7.

DOIPubMed -

100. Fettig A, Pogrel MA, Silverman Southward Jr, Bramanti TE, Da Costa M, Regezi JA. Proliferative Verrucous leukoplakia of the gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;90:723-30.

DOIPubMed -

101. Hansen LS, Olson JA, Silverma Due south, Jr. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. A long-term study of xxx patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1985;threescore:285-98.

DOI -

102. Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo K, Griffiths M, Sugerman PB, Thongprasom K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: report of an international consensus coming together. Part 1. Viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2005;100:40-51.

DOIPubMed -

103. Terai M, Takagi M. Human papillomavirus on oral crenel. Oral Med Pathol 2001;six:i-12.

DOI -

104. Castro TP, Bussoloti Filho I. Prevalence of human being papillomavirus (HPV) in mouth and oropharynx. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2006;72:272-82.

DOI -

105. Eversole LR, Laipis PJ. Oral squamous papillomas: detection of HPV DNA past in situ hybridization. Oral Surg Med Oral Pathol 1998;65:545-50.

DOI -

106. Syrjänen S. Human papillomavirus infections and oral tumours. Med Microbiol Immunol 2003;192:123-8.

DOIPubMed -

107. Chang F, Syrjänen S, Kellokoski J, Syrjänen K. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infections and their associations with oral affliction. J Oral Pathol Med 1991;20:305-17.

DOIPubMed -

108. Manganaro AM. Oral condilloma accuminatum. Gen Dent 2000;48:62-4.

PubMed -

109. Eversole LR. Papillary lesions of the oral crenel: relationship to human papillomaviruses. J Calif Paring Assoc 2000;28:922-7.

PubMed -

110. Resnik DA. Oral manifestations of HIV Disease. Top HIV Med 2006;xiii:143-8.

-

111. Padayachee A, Sanders CM, Maitland NJ. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) investigation of oral verrucae which incorporate HPV types 2 and 57 by in situ hybridization. J Oral Pathol Med 1995;24:329-34.

DOIPubMed -

112. Garcia-Corona C, Vega-Memije E, Mosqueda-Taylor A, Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Rodríguez-Carreón AA, Ruiz-Morales JA, Salgado North, Granados J. Clan of HLA-DR4 (DRBI*0404) with human being papillomavirus infection in patients with focal epithelial hyperplasia. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:1227-31.

DOIPubMed -

113. Schwenger JU, Von Buchwald C, Lindeberg H. Oral focal epitelial hyperplasia. Any chance of conclusion with oral condylomas? Ugeskr Laeger 2002;164:4287-90.

PubMed -

114. Pfister H, Heiltich J, Runnae U, Chilf GN. Characterization of homo papillomavirus type 13 from focal epithelial Heck's lesions. J Virol 1983;47:363-6.

PubMed PMC -

115. Beaudenon South, Praetorius F, Kremsdorf D, Lutzner Chiliad, Worsaae Due north, Pehau-Arnaudet G, Orth G. A new blazon of human papillomavirus associated with oral focal epithelial hyperplasia. J Invest Dermatol 1897;88:130-5.

DOI -

116. Fakhry C, Gillson ML. Clinical implications of man papillomavirus in head and neck cancers. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2606-11.

DOIPubMed PMC -

117. Schwartz SR, Yueh B, McDougall JK, Daling JR, Schwartz SM. Man papillomavirus infection and survival in oral squamous jail cell cancer: a population-based written report. Otolaryngol Head Cervix Surg 2001;125:1-nine.

DOIPubMed -

118. Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Haffty BG, Kowalski D, Harigopal M, Brandsma J, Sasaki C, Joe J, Army camp RL, Rimm DL, Psyrri A. Molecular classification identifies a subset of human being papillomavirus--associated oropharyngeal cancers with favorable prognosis. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:736-47.

DOIPubMed -

119. Worden FP, Kumar B, Lee JS, Wolf GT, Cordell KG, Taylor JM, Urba SG, Eisbruch A, Teknos TN, Chepeha DB, Prince ME, Tsien CI, D'Silva NJ, Yang Grand, Kurnit DM, Mason HL, Miller TH, Wallace NE, Bradford CR, Carey TE. Chemoselection as a strategy for organ preservation in avant-garde oropharynx cancer: response and survival positively associated with HPV-16 re-create number. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3138-46.

DOIPubMed PMC -

120. Rosenthal DI, Harari PM, Giralt J, Bell D, Raben D, Liu J, Schulten J, Ang KK, Bonner JA. Clan of human papillomavirus and p16 status with outcomes in the IMCL-9815 stage Three registration trial for patients with locoregionally avant-garde oropharyngeal squamous prison cell carcinoma of the caput and neck treated with radiotherapy with or without cetuximab. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1300-8.

DOIPubMed PMC

Cite This Article

Ramírez-Pérez FA. The role of homo papillomavirus in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Plast Aesthet Res 2016;3:132-41. http://dx.doi.org/ten.20517/2347-9264.2016.17

Views

17201 Downloads

713 Citations

1 Comments

1 Comments

0

0

Download and Bookmark

Download

Download PDF

Download PDF  Add to Bookmark

Add to Bookmark

Article Admission Statistics

Full-Text Views Each Month

PDF Downloads Each Calendar month

Quantities of Citations Each Yr

* All the data come up from Crossref

Source: https://parjournal.net/article/view/1381#:~:text=Conclusion%3A%20HPV%20divides%20OSCC%20in,risk%20of%20death%20and%20recurrences.

0 Response to "The Role of Human Papillomavirus in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Review)"

Post a Comment